The Gaze from the North: Kuo Hsueh-Hu and His Southern World

- 九月 10, 2020

- Exhibitions, 郭雪湖

Duration:2020.09.05 (Sat.)- 2020.10.25 (Sun.)

Opening:2020.09.05 (Sat.) 3pm

Venue:Liang Gallery 1F, 2F

Artist:KUO Hsueh-Hu, KUO LIN A-Chin

Curator:WU Chao-Jen

Forum:2020.09.12 (Sat.) 3pm

“The Debate of the Orthodoxy of Chinese Painting–The Past, Present, and Prospect of Gouache Painting”

Speaker:Curator WU Chao-Jen

Assistant Professor of Dept. of Fine Arts, Tunghai University

PAN Hsin-Hua

Artist

Lecture:2020.09.20 (Sun.) 3pm

“The Artistry of Ink: The Refreshing and Rebirth of Classic Oriental Paintings”

Speaker:LEE Chen Huei

Professor/ Chair of Dept. of Fine Arts, Tunghai University

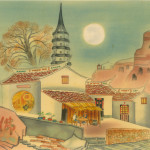

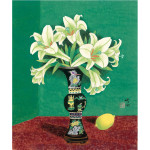

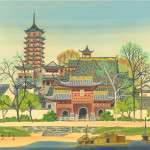

With the best support from Kuo Hsueh-Hu Foundation, The Gaze from the North: Kuo Hsueh-Hu and His Southern World will open on September 5 at Liang Gallery in Neihu, Taipei. The exhibition curated by WU Chao-Jen, the Assistant Professor of Department of Fine Arts at Tunghai University, features the masterpieces by KUO Hsueh-Hu (1908-2012) of his years in Taiwan and overseas, including Stream through Pine Ravine and Scenery Near Yuan Shan (preliminary drawing) in 1927, with which he was selected by the first Taiwan Art Exhibition, and Chinese Garden in 1932, along with a great number of the rarely-seen flower paintings and travel paintings. The exhibition also includes 7 artworks by Madame LIN A-Chin, the wife of KUO Hsueh-Hu, presented as a testimony to the viewers of how the seven decades of a marriage of mutual understanding had supported the husband and wife through the challenges in life as well as in arts.

The North-versus-South conflict has started long time ago in the Chinese history. It is why the Huaxia-centered civilization sees the people from the South as Nanman (南蠻, literally the barbarians in the South, similar examples can be found in Beidi of the North, Xirong of the West, and Dongyi of the East). Since the Age of Discovery starting from the 15th Century, the newly developed geographical knowledge and the studies of Astrometry, which could be traced back to the Renaissance, have brought a radical change to a centralized worldview. During the Azuchi–Momoyama period in the history of Japan (1568-1603), the traders and sailors from Portugal and Spain were also called “Nan-ban” (南蠻) by the Japanese, simply because the European naval and trading fleets often came from the south through either the Taiwan Strait or the Philippine Sea as they entered Japan’s territorial waters.

As a result of the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894, Taiwan and Penghu Islands were ceded to Japan by the Qing Dynasty, followed by the fifty years of Japanese occupation. It was when under the Japanese rule that KUO Hsueh-Hu was introduced to the world of arts and started the most prolific stage of his artistic career. As the Pacific War came to an end in 1945, Taiwan was handed over to the Nationalist government of China. However, a revolt broke out against the Chinese government in 1947, known as the February 28 Incident, taking numerous lives including the Taiwanese painter CHEN Cheng-po who had received education in Japan but killed by gunshot in Chiayi. The follow-up island-wide massacre and the imposition of Martial Law starting in 1949 soon caused the Taiwanese artists who had grown up in the Japanese occupation and had received the Japanese art education to panic. During the 1950s, the “Provincial Art Exhibition” began to question the categorization of “Dongyang painting” (東洋畫, often used to refer to the painting featuring a Japanese style) by Taiwanese painters, consequently leading to the argument over the “legitimate national painting.” The controversy was heated up when the Provincial Art Exhibition jury committee experienced a structure shift as the Taiwanese painters in the committee were gradually replaced by the mainlanders. Therefore, the determined KUO Hsueh-Hu left Taiwan for Japan in the October of 1964, where he had lived away from home for 23 years until his return in 1987 on the eve of the announced lifting of Martial Law.

How can we define the relation among Dongyang painting, gouache painting, Japanese painting, and the “legitimate” national painting? Why did the Institution of the Provincial Art Exhibition committee drive KUO Hsueh-Hu away from his hometown? How did “the gaze from the north,” or should we understand it as the art education and imperialism imposed during the Japanese occupation, shape the exquisiteness of KUO’s arts as it also confined his visual aesthetics? Through its exhibits and curatorial narrative, The Gaze from the North: Kuo Hsueh-Hu and His Southern World hopes to offer a different academic perspective for the art history of Taiwan.