A Performance in the Church — HSU Chia-Wei’s solo exhibition

- 十一月 06, 2021

- Exhibitions

Date:2021.11.13 (Sat.)—2020.12.19 (Sat.),Tuesday to Sunday 11:00-18:00

Opening:2020.11.07 (Sat.) 15:00

Address:Liang gallery 2F,No. 366, Ruiguang Road, Neihu District, Taipei City, 11492

Artist: HSU Chia-Wei

After Hsu Chia-Wei made his The Story of Hoping Island in 2008, he noticed the Fort Noord-Holland built in the 17th Century (Fort San Salvador in 1642) on Hoping Island, which soon raised his interest in exploring the complex network of the Dutch East India Company and how it was connected to the old city of Malacca built in 1641 and the war between Cambodia and the Dutch in 1643. Within these interrelated networks, the marine economy of the European great powers institutionally depended on the East India Company of each country, while the companies’ play in the sea trade even indirectly helped to expand the impact of the sea powers of colonial empires on East and Southeast Asia in the fields of science, art, and politics.

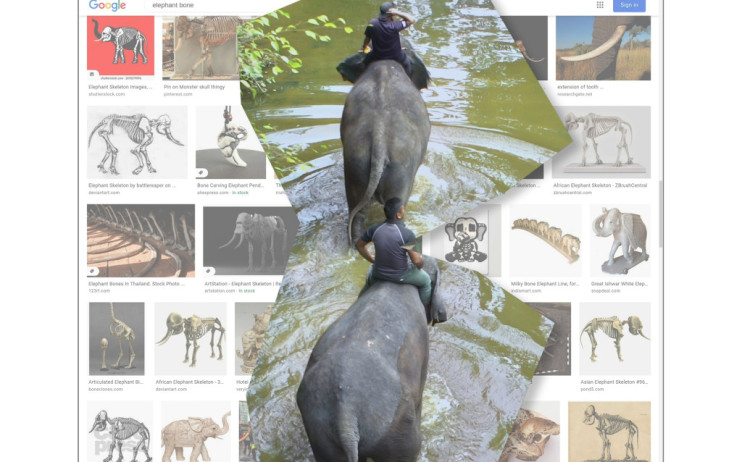

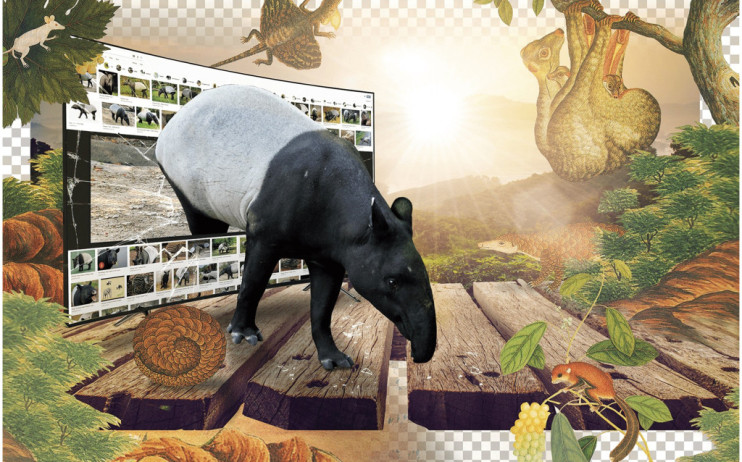

The exhibition features more than ten pieces/sets of works, created by the artist who has spent nearly two years contextualizing the materials within the abovementioned framework: the video and installation in A Performance in the Church not only demonstrate how the archaeological team apply modern technology to archaeology, but is more about presenting the way how the artist sees, uses, and transforms these videos and sounds to the viewers; in Search for Shipwrecks, the artist follows the research materials documented in Green Island Township Chronicle about an underwater archaeological survey and discovery of a centuries-old sunken ship, as he adopts modern technology to imagine and simulate a spatiotemporal world we have never experienced. The starting point of Samurai and Deer is the barter economy practiced by the Dutch East India Company across and around Asia, such as trading Indonesian spices for Taiwanese deerskins before selling the deerskins to the Japanese for silver as capital for future investment. As the supply of deerskins from Taiwan could no longer meet the rising demand, the Dutch East India Company turned to Cambodia with an attempt to have a control on its local deerskin market, unavoidably followed by a consequential series of conflicts. Meanwhile, Black and White—Malayan Tapir brings us back to the days when the British East India Company chose Singapore as a commercial base to develop Southeast Asia, thus starting to collect data and build museum-based archives to establish its local flora and fauna studies. William Farquhar (1774-1839), the first commandant of the British East India Company stationed in Malacca, once hired a Chinese painter for a comprehensive visual documentation and categorization of the species found in the Malay Peninsula, and the archive included an endemic black and white creature – the Malayan tapir. With its encyclopedic narrative, the artwork intends to deal with the relationship between human and non-human or nature as an equality rather than one being subject to the other, while it further explores how modern people change their way of viewing images. By featuring scenes and images from the National Gallery Singapore, the National History Museum, Singapore Zoo, search engines, and multiple window-browsing, it renders a political relationship connecting the history of menageries in Southeast Asia and the colonial eras.

Although we cannot relive the past again, modern archaeology, especially with the support of advanced technology and interdisciplinary studies, can almost materialize an era or a world we have never been before and offer different levels of imaginations of the scenarios at that time. The artist Hsu Chia-Wei plays with the uncertainty and authenticity of historical representation in archaeology, with which he borrows the concept of “internet of Things” where heterogeneous items, events, and units are interconnected to transform the intangible thoughts and ideas into the tangible materials as finalized in videos, images, sculptures, and installations. The exhibits in The Story of Hoping Island draw on the trends of open and interdisciplinary technologies of todays’ archaeological studies, taking it as a departure to reach beyond history and politics into the field of sonics and contemporary art – a continuous staging made possible from the untraceable scenes

Oder post

Oder post